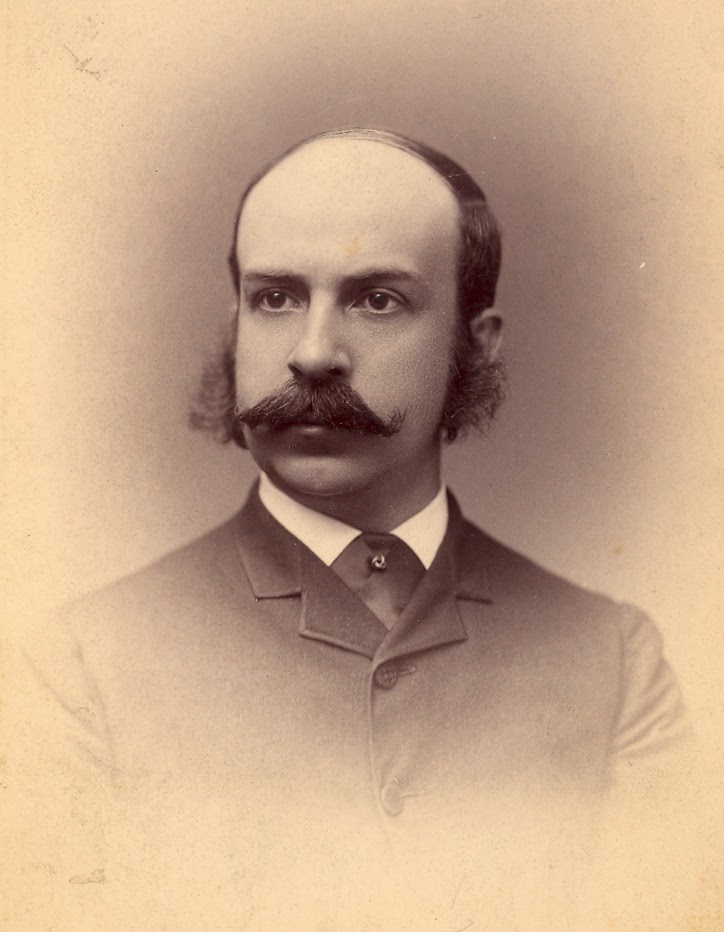

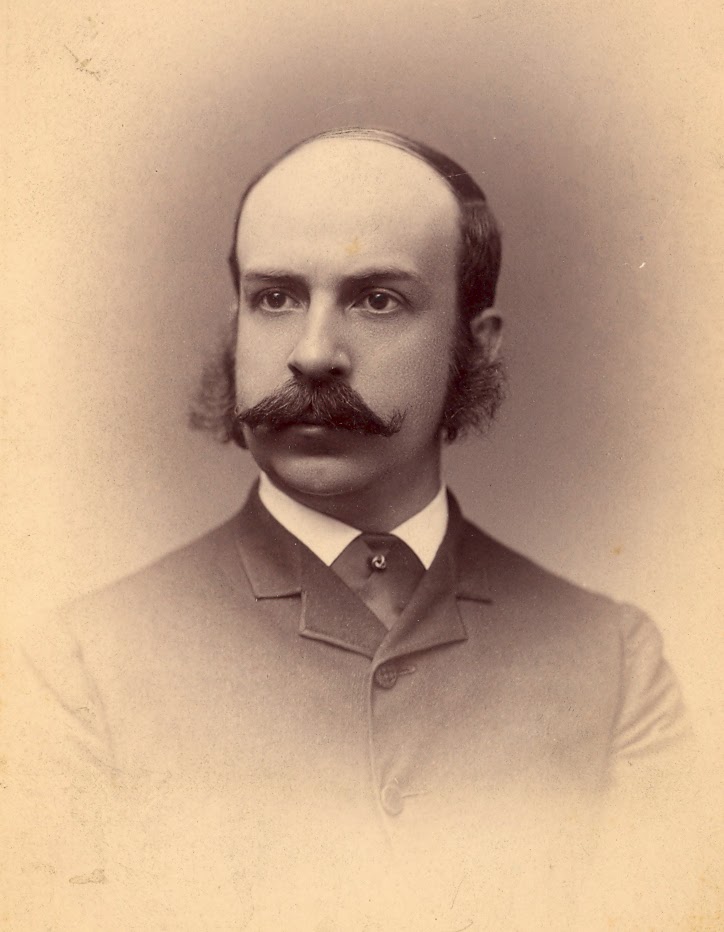

Dr. Albert Philson Brubaker

born: 12 August 1852 in New Lexington, Somerset County, PA

died: 29 April 1943 in Philadelphia, PA

buried: Laurel, Philadelphia

father: Dr. Henry Brubaker (1827-1889)

father: Dr. Henry Brubaker (1827-1889)

mother: Emeline Philson (1830-1898)

wife: Edith Bentley Needles (1856-1932), married 27 September 1883; no children

1874 – educated at Jefferson Medical CollegeIn 1883, Albert married Edith Bentley Needles, a Quaker whose family can trace its lineage back to Francis Cooke (who came to America on the Mayflower).

In 1888, Albert wrote A Compend of Human Physiology (published by P. Blakiston, Son & Co., 1012 Walnut Street). In the book, Albert is listed as “Demonstrator of physiology in the Jefferson Medical College; Professor of physiology, Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery; Member of the Pathological Society of Philadelphia.”

My great-grandfather, Edwin Schall Brubaker, is seated in the bottom row, between two women. I believe the man standing at right is his brother, Dr. Albert Philson Brubaker.

The following is copied from the Powelton Village history blog.:

Our Dr. Frankenstein? A True Tale for Halloween

In 1883, he married Edith Needles, the daughter of a druggist. They lived with her family for a number of years. When the Drexel Institute was opened, he became the lecturer on Physiology and Hygiene. It was probably about this time that they moved to 105 N. 34th St. where they lived for about 35 years. Edith, meanwhile, continued her studies by taking courses in biology at the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1897, Albert joined the faculty at Jefferson. He had already held various positions there and it was at Jefferson that he pursued his research on physiology. He also published several textbooks that were widely used and republished numerous times. He was a member of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the Academy of Natural Sciences, the American Physiological Society and the American Philosophical Society. In his later years, he was active in the Ethical Culture Society. In 1916, the graduating class at Jefferson dedicated a volume to him. In it they described him as a “strict disciplinarian… yet most affable and considerate towards students and colleagues; tolerant of all truths, endowed with singularly happy equipoise, broad sympathies and all-around completeness.” Edith was active in the New Century Club and became its president in 1905. Later, she was very active in the Visiting Nurses Association. In about 1918, they moved to 3426 Powelton Ave. where they lived for many years.

Brubaker was a scientist who wanted to understand the workings of the human body. One of his more unusual experiments examined the role of electricity in animating the body. It was observed by a reporter from the Philadelphia Inquirer and described in an article on the front page in January 1900. Although it was a serious investigation, the story reads more like the script for a scary silent film.

"When the negro policy dealer, Robert W. Brown, who murdered his wife, Lucinda, more than a year ago, was being dragged to the gallows in Moyamensing Prison on Thursday, he shudderingly shrieked, ‘My body will go to the dissecting table – to the dissecting table!’

|

| (Phila. Inquirer, Jan. 12, 1900) |

"His religious advisers admonished him to think of his soul and not of his body.

"Pleading for delay for both soul and body, the wretched stabber fell through the fatal trap of the very moment when he turned his head to implore the keeper at his side for more time to speak.

"In this act the knot back of his left ear slipped to the base of the brain, midway between the ears, and consciousness expired instantaneously at the end of the rope.

"There were those who wanted, in the interest of science, to give the murder is wished for opportunity to complete the suspended speech. Not a second was wasted after he was pronounced dead. An ambulance, with clanging bell and the right-of-way, flew through the streets to the Jefferson College. In ten minutes after he was legally dead he was resting on a table in the physiological laboratory.

"Around the table were three of the most famous physiologists in the scientific world. They were Drs. Judson Deland, Albert P. Brubaker and A. Hewson. Dr. Deland had charge of the demonstration.

"Pleading for delay for both soul and body, the wretched stabber fell through the fatal trap of the very moment when he turned his head to implore the keeper at his side for more time to speak.

"In this act the knot back of his left ear slipped to the base of the brain, midway between the ears, and consciousness expired instantaneously at the end of the rope.

"There were those who wanted, in the interest of science, to give the murder is wished for opportunity to complete the suspended speech. Not a second was wasted after he was pronounced dead. An ambulance, with clanging bell and the right-of-way, flew through the streets to the Jefferson College. In ten minutes after he was legally dead he was resting on a table in the physiological laboratory.

"Around the table were three of the most famous physiologists in the scientific world. They were Drs. Judson Deland, Albert P. Brubaker and A. Hewson. Dr. Deland had charge of the demonstration.

"A Startling Question.

"Could motion and life be restored to that inanimate body?

"For an answer to this question the three scientists devoted their energies and resources of their skill and genius.

“They had all taught that certain nerve centres controlled motion and action. In that eminent body, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, of which the professors are members, the theory has often been advanced that there is no physiological necessity for early death. Here was a subject dead to all ordinary tests. Was he scientifically dead?

"A sharp wire, charged with electricity, was applied to the various nerve centres of the body and brain. A superstitious layman would have been horrified at the result. Brown raised first his right arm and then his left. His had moved. His mouth twitched in a compulsive grin. the cords of the neck swelled and the mouth opened as if he would complete his interrupted speech on the scaffold. The hands clenched one after the other. A leg was drawn up and then extended.

“Unceasingly electric wire prodded centre after centre in the nervous organism. One would have thought that a new Cagliostro was at work. At a fresh touch from the thaumaturgist plying the needle the body sat upright.

"For an answer to this question the three scientists devoted their energies and resources of their skill and genius.

“They had all taught that certain nerve centres controlled motion and action. In that eminent body, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, of which the professors are members, the theory has often been advanced that there is no physiological necessity for early death. Here was a subject dead to all ordinary tests. Was he scientifically dead?

"A sharp wire, charged with electricity, was applied to the various nerve centres of the body and brain. A superstitious layman would have been horrified at the result. Brown raised first his right arm and then his left. His had moved. His mouth twitched in a compulsive grin. the cords of the neck swelled and the mouth opened as if he would complete his interrupted speech on the scaffold. The hands clenched one after the other. A leg was drawn up and then extended.

“Unceasingly electric wire prodded centre after centre in the nervous organism. One would have thought that a new Cagliostro was at work. At a fresh touch from the thaumaturgist plying the needle the body sat upright.

“Every Sign of Life.

“Amazing enough was all this. There was more. The eyes opened. The

heart beat. There seems to be breath, for the organs of respiration were

agitated. “Would he walk? Would he talk?

“But, placed on the floor, the body fell back limp. The lips opened without sound. Science has demonstrated wonders, but life could not be brought back with motion. The soul has gone beyond returning breath. The electric needle and made Brown do everything but walk and talk.

“In less than an hour the nerve centres themselves became dead. The three scientists surrendered the effort at resuscitation. The limp body of the murder was removed to the anatomical department on the top floor.

“There Dr. Brubaker, who is the demonstrator of physiology in the Jefferson Medical College, and the author of text books used in that institution, lectured yesterday afternoon to the second and third year men on Brown's body. He explained to them the operations practiced upon the subject, and the resulting phenomena. Brown had died in a religious hysteria. By the slipping of the noose the neck had not been broken. The brain had been congested. The heart has been remarkably strong, beating fifteen minutes after drop fell, and artificial resuscitation afterward did not seem difficult."

(Phila. Inquirer, Jan. 13, 1900, pg. 1)