Joseph DeVenny Brubaker, Sr.

born: 12 July 1897 in Beaver County, Pennsylvania

died: 6 Sept. 1978 in Beaver County, Pennsylvania

buried: Beaver Cemetery and Mausoleum, Beaver, PA

father: Edwin Schall Brubaker (1864-1939)

mother: Carrie Josephine DeVenny (1871-1925)

wife: Helen Marquis McDanel (1897-1958), married 24 August 1921; Gertrude Wagoner (1916-2003), married about 1960.

children: Joanne (born 1931, died at birth), Joseph DeVenny Brubaker, Jr. (b. 1933), and John Robert “ Bob” Brubaker (b. 1935)

siblings: Sarah Elizabeth Brubaker (1896-1971) and a half-brother by Edwin's first wife, Henry Sampson Brubaker (1890-1969)

Joseph DeVenny Brubaker, Sr. is my paternal grandfather. He was the second child of Edwin Schall Brubaker and his second wife, Carrie Josephine DeVenny, and was reared in New Brighton, Pennsylvania.

|

| Joe and his sister Sarah Elizabeth |

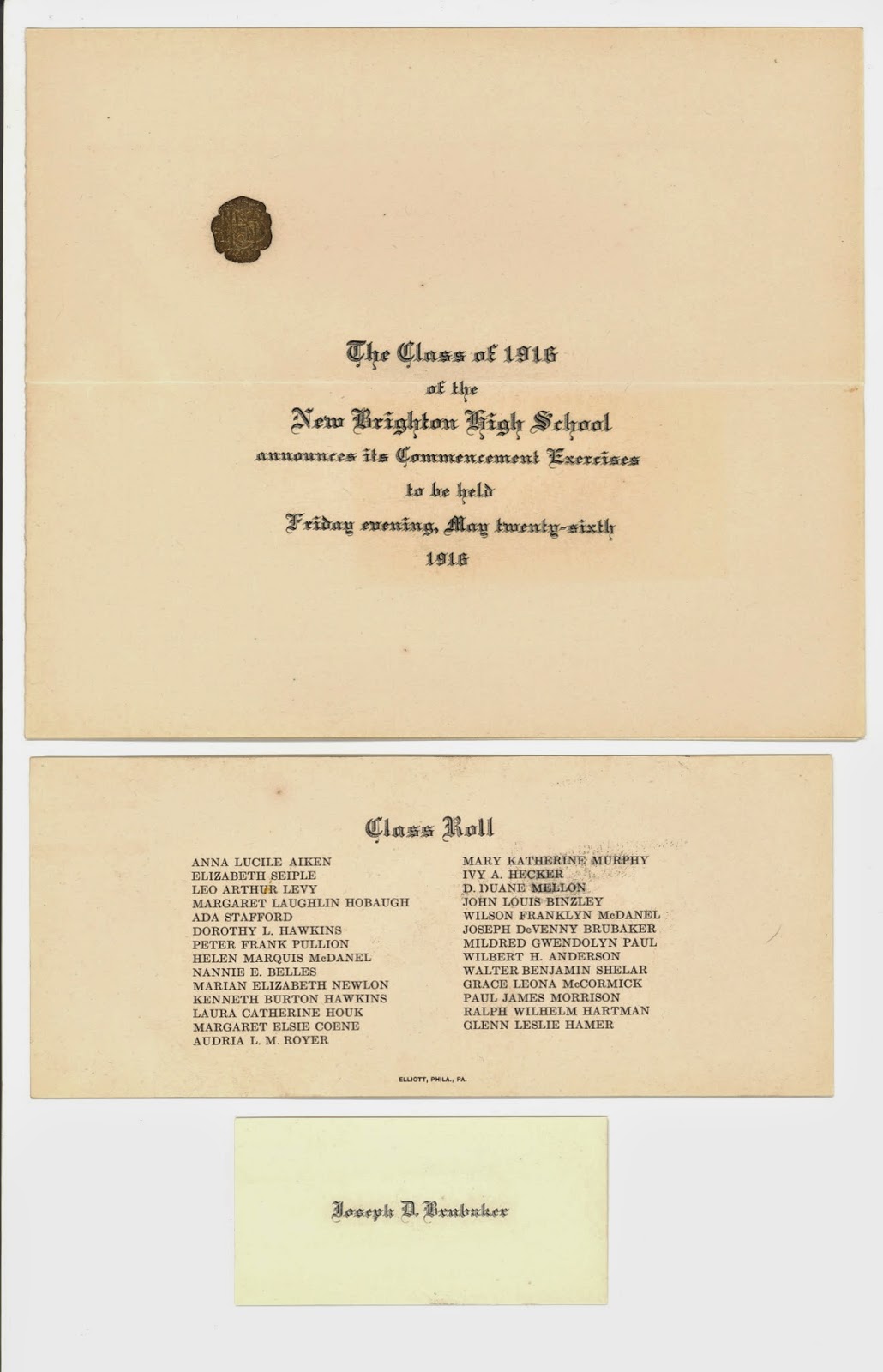

He graduated from New Brighton High School in 1916. This photo from my grandmother Helen’s photo album shows her with Joe (second from left), her sister Marion, Shad (Marion’s husband), and John (the driver). This photo was probably taken about 1916.

He served in the Marine Corps in Haiti during World War I, where he contracted malaria. My father says he never could drink gin after that, as it reminded him of the quinine treatment he received. Some of the history of the U.S. involvement in Haiti during this time is covered on Wikipedia.

Upon returning to Beaver County, Joe worked as a bank teller and married his high school sweetheart, Helen Marquis McDanel, on 24 August 1921. He worked his way up into bank management, and they had three children (the first, JoAnne, died at birth in 1931).

Joe was an avid golfer, and was very artistic.

|

| Helen owned these two houses, and Helen and Joe raised their two boys in one of them. |

| ||

| Helen and Joe with Joe Jr. (top) and Bob, about 1947 |

| |||||||

| With Helen, possibly at Bob and Ellie’s wedding in 1957 |

|

| 4 N. Old Oak Drive, Patterson Heights |

|

| Joe with me, probably Christmas 1964 |

After Helen’s death in 1958, Joe met Gaby Wagoner while on a cruise to Hawaii, and married her. I believe it was her second marriage, but have had no success in finding details of it.

|

| Gertrude “Gaby” Brubaker, Joe’s second wife |

Joe died in 1978.

Transcription:

Joseph Brubaker, Ex-Banker, Dies

Beaver Falls – Joseph D. Brubaker Sr., former director and vice chairman of the board of Century National Bank and Trust Co., of Rochester, Pa., died yesterday at his home.

Mr. Brubaker, 81, of North Old Oak Drive, Patterson Heights, also was former director and treasurer of Tower Federal Savings and Loan Association abdn past president of the Beaver County Bankers Association. Mr. Brubaker was a member of the First Presbyterian Church, New Brighton, Beaver Valley Country Club, Pittsburgh Athletic Association, and several community organizations.

Surviving are his wife, Gertrude; two sons, Joseph D. Jr. of Glenrock, NJ, and Robert of Mt. Lebanon, and seven grandchildren.

Friends will be received from 7 to 9 tonight and from 2 to 4 and 7-9 p.m. tomorrow at Donald D. Druschel Funeral Home, 1612 Third Ave., New Brighton. Services will be at 10:30 a.m. Saturday at the First Presbyterian Church, Third Avenue, New Brighton.

Burial will be in Beaver Cemetery, Beaver.